In order to have meaningful negotiations it is crucial to understand the mechanics of a purchase price and what elements can impact the underlying price. Many deals collapse due to inability between a Buyer and Seller to communicate and negotiate on the purchase price. This often happens when a large corporate tries to acquire a smaller self-made entrepreneurial business. The first one has significant transaction experience and speaks in technical terms, while the last only wants to know the money he will receive.

Knowing how a purchase price is structured and which elements impact the price will ensure you reaching the highest value for your business.

Cash- and debt-free basis

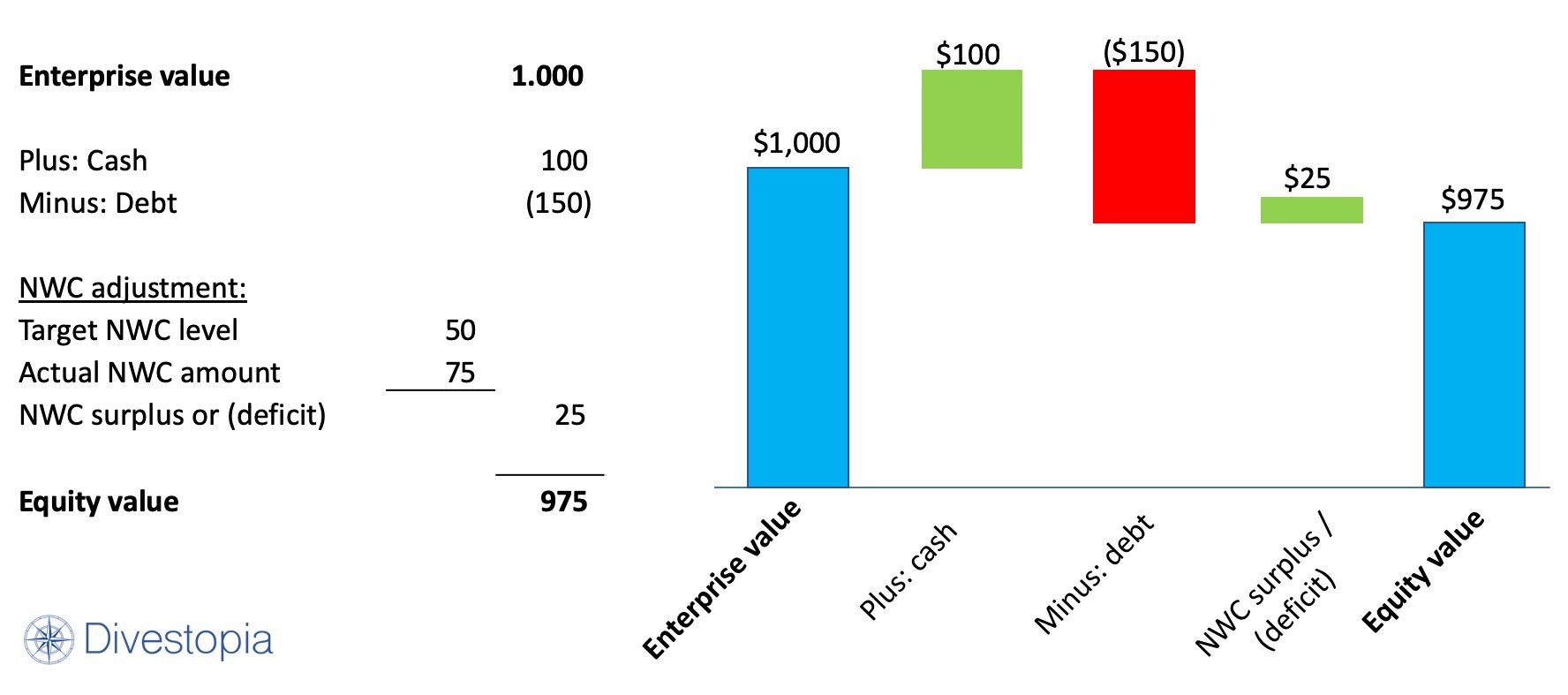

Most transactions and M&A deals are on a cash-free and debt-free basis. In short, this means the Seller receives all cash and repays all debt at the time of sale of the Company. If you receive an offer saying your business is worth $100m on a cash- and debt-free basis, this does not mean you eventually get $100m. It only means an investor values your business at $100m (so-called enterprise value). You need to add the cash and deduct any debt balances of your Company before you arrive at the net purchase price (so-called equity value). This goes further than just your reported cash- and debt-balances and also includes cash-like and debt-like items.

The offer also includes a mentioning to net working capital (NWC) and will state something like “the business needs to have a normalized level of net working capital at closing”. This means there needs to be sufficient working capital in the Company at the moment of close. Any difference between the required level of NWC and the actual level of NWC at closing, is either deducted or added to the purchase price.

Enterprise value versus equity value can be compared to a house with a mortgage debt. The value of the house is the enterprise value. Deducting the mortgage debt leaves the equity value.

Enterprise to equity value bridge

To simplify this a so-called enterprise value to equity value bridge (EV to equity bridge) is used. An example of this bridge is:

For an Excel template of a EV to Equity bridge click here.

The underlying value of your business is expressed as the enterprise value. This is the value excluding any debt or cash your Company has. For listed companies this is the market capitalization (outstanding shares times the current share price), excluding debt and cash. For private companies this is generally calculated with a discounted free cash flow valuation model. Meaning discounting the future free cash flows of your business. This value is then divided through the last year EBITDA your Company realized to get to an EBITDA multiple (so-called EV/EBITDA multiple). This EBITDA number and the multiple is extremely important for negotiation purposes.

Adjusted EBITDA

In the offer letter a potential Buyer includes the EBITDA number and the multiple he used to calculate the enterprise value of your business. The EBITDA is derived from numbers you provided (either in the teaser, the CIM or other sell side reports). One of the main purposes of the buy-side due diligence is to assess this EBITDA number and to check if it is reflective of the recurring and operational earnings of your business. In other words, the EBITDA needs to be exclusive of any non-recurring, one-off or non-operational items. This EBITDA is called the Adjusted EBITDA.

There are no strict rules for calculating Adjusted EBITDA and the playing field is gray. All can be considered as long you provide clear argumentation why something is operational and recurring (or excluded items are non-operational, non-recurring).

For example, if you recorded a provision for a doubtful debtor, but released this amount in the income statement a year later because the debtor paid, a Buyer will adjust this to EBITDA (as both the recording and the release of the provision had nothing to do with actual business, it was just an accounting entry).

Examples of common EBITDA adjustments are:

- Advisory costs related to the deal (non-operational and not related to the business)

- Release of provisions (non-cash)

- Impairments (one-off and non-cash)

- Litigation expenses (depending on occurrence, but often considered one-off)

- Severance payments (one-off)

- Recruitment costs for key employees (one-off)

- Owner salaries and bonuses (if higher than what is common in the market; this depends on how your business is managed post-acquisition)

- Related party lease or rent (if it differs from common market price. An example is the building is rented through another entity owned by the same selling shareholder)

- Proceeds on the sale of assets (non-operational and non-recurring)

- One-off professional fees (for example, one-off costs for implementing a new ERP system)

- Other items in your income statement (often are non-operational and non-recurring).

There is no clear definition or rules regarding what can be adjusted in EBITDA. If you paid-out a bonus to your employees because of an exceptionally high result you might say this is one-off. A Buyer will say this is recurring and part of doing business. Or a write-off relating to a customer that went bankrupt, while you will say this is one-off, a Buyer will say this is part of normal business.

Maybe you incurred a lot of marketing costs for a new product or service and consider this to be one-off and should be borne by a Buyer. A Buyer will say this is part of normal business for a growing Company.

Be sure of your adjustments and have clear argumentation why they should be considered non-recurring or non-operational. Being too aggressive in your adjustments risks a potential Buyer questioning all of your adjustments.

How do EBITDA adjustments impact price

So, how do EBITDA adjustments impact the purchase price? As mentioned before, the offer letter you receive includes an EBITDA number and a multiple to arrive at the enterprise value. If the potential Buyer finds any additional EBITDA adjustments, they use the multiplier from the offer letter to change the purchase price.

If a Buyer after doing its due diligence finds adjustments which decrease EBITDA by $100, this decreases the purchase price by $100 times the multiple indicated in the offer letter. If the multiple is 10, the purchase price will be deducted by $1,000 (adjustment of $100 times the multiple of 10).

As you can imagine this has a huge impact on the purchase price. That is why it is extremely important to know your numbers before starting with the diligence process. Be sure you identified all non-recurring and non-operational items and understand the impact.

Repair and Maintenance costs

In smaller businesses Repair and Maintenance costs (R&M costs) are expensed when occurred in order to decrease profits and taxes payable. Whereas following accounting principles these costs can be capitalized and depreciated, and by so-doing increasing EBITDA. While this increases your EBITDA remember that the underlying value of your business (i.e., the enterprise value) is calculated based on free cash flows, which are calculated as EBITDA minus capex and adding the NWC fluctuation.

So, you can increase EBITDA by adjusting the R&M costs and saying they should be capitalized, a smart investor just adds that to the capex line and the resulting free cash flow number is the same. In other words, this has no impact on the valuation of your business. These costs have to be paid either way, whether you capitalize or expense it is just accounting.

Research and Development costs

The same goes for capitalizing IT development or Research and Development costs (R&D costs). However, in the case a potential Buyer needs to justify the EBITDA multiple to its internal investment committee or you want to show high Adjusted EBITDA numbers in your sell side report, this could be considered as it does lower the multiple (i.e., presenting a higher EBITDA amount).

While not impacting the underlying valuation of your business it is always better to present a higher EBITDA by capitalizing R&M or R&D costs.

Other EBITDA definitions

Many more EBITDA definitions are used in the M&A world. Some other important definitions are pro forma EBITDA and run-rate EBITDA.

Pro forma EBITDA

A pro forma EBITDA is used to present like-for-like earnings of your business. You adjust the EBITDA to present the EBITDA how it would be in the new situation.

Some examples of pro forma EBITDA adjustments:

- Your Company acquired another company during the last year. The financials of this acquisition are consolidated in your numbers as from date of acquisition (lets say July). When looking at your full year financials this means that only half a year numbers of the new acquisition are included. A pro forma adjustment adds the first half year numbers of the acquired company to show full year results.

- Related to acquisitions, it could be that the synergies from a historic acquisition you performed are not yet realized. For example, headcount savings. A pro forma EBITDA adjustment shows how the financials of your business would look like if all these synergies are realized.

- Currently, you as an owner are earning more than what is common in the market. Post-acquisition you continue with the Company but will be employed with a lower salary. The adjustment to present the lower salary rather than the higher current salary is a pro forma adjustment.

- You do not want to sell your entire business but only one business unit (carve-out sale). The costs which are required to operate that business unit on a stand-alone basis could be adjusted through a pro forma adjustment.

As they relate to the future, pro forma adjustments have a lesser degree of certainty than traditional EBITDA adjustments. Traditional EBITDA adjustments were incurred historically and can be supported by additional documentation. For example, for one-off professional fees you can present the invoice of the supplier.

Given the lesser degree of certainty, present the pro forma EBITDA separately from Adjusted EBITDA. This way a potential Buyer can make his own assessment of these adjustments.

Run-rate EBITDA adjustments

Run rate adjustments use a historically realized result and recalculate it for the whole financial year. These type of adjustments are common in sectors with recurring revenues and customers with subscriptions.

For example, in January you have 10 customers each with a monthly subscription revenue of 5 dollars. In December, this has grown to 25 customers each with a monthly subscription revenue of 5 dollars. The number of customers has grown evenly during the year, so the full year reported revenue is not representative of the revenues that can be realized with the customer base you have at the end of the year. The run-rate revenue would be 125 dollar, being the 25 customers in December against the monthly revenue of 5 dollars per customer. The difference between your reported revenue and the run-rate revenue is the run-rate adjustment.

A run rate adjustment is a very valuable metric to present the revenue potential with the customer base you already have. Other examples can be found in cost savings. If during the year you moved to a smaller office with cheaper rent, the reported yearly rental cost would be higher than the rental cost in the next year. A run-rate adjustment would adjust your rental costs to show only the lower new agreed yearly rental costs.

Run-rate adjustments are extremely useful to show the real underlying potential of your business, especially when you only recently introduced new cost savings initiatives or have a large growing customer base which shows recurring revenues

Synergies

The enterprise value presents the value of your business based on its expected future cash flows. It does not includes a premium or synergies a potential Buyer expects to realize. The enterprise value investors mention in their offers will include some premium on top of the “true” enterprise value. Especially, in an auction process with many potential Buyers a premium needs to be paid to be the ultimate Buyer. This premium is not visibly shown in the offers. Additionally, a Buyer is unwilling to pay its full synergy saving to the Seller, as this regards future savings which still need to be realized.

Find more on:

- Free M&A Excel templates for download

- Normal level of net working capital at Closing

- Locked box versus completion accounts

- Choosing and preparing a virtual data room